Why Do We Need MCMC?

In short, because many distributions are only known in unnormalized forms, making traditional sampling/integration methods ineffective.

Goal: Sample from a complex distribution $\pi(x)$ (often only known as “unnormalized” $\tilde\pi(x)\propto \pi(x)$), or compute expectation/marginal:

$$ \mathbb{E}_\pi[f(X)] \;=\; \int f(x)\,\pi(x)\,dx. $$Reality Difficulties:

- High Dimensionality: As dimensions increase, grid/numerical integration explodes exponentially;

- Unknown Normalization Constant: In Bayesian context, the denominator $p(y)=\int p(y\mid \theta)p(\theta)\,d\theta$ in posterior $\pi(\theta\mid y)\propto p(y\mid \theta)p(\theta)$ is often intractable;

- Multi-modal/Strong Correlation: Variance of Rejection Sampling or Importance Sampling becomes huge or suffers from “weight degeneracy”.

Core Idea of Monte Carlo: Given samples $x^{(1)},\dots,x^{(T)}\sim \pi$, we can use sample mean

$$ \frac{1}{T}\sum_{t=1}^T f\!\big(x^{(t)}\big) $$to approximate $\mathbb{E}_\pi[f(X)]$. The problem is how to sample from $\pi$? This is exactly what MCMC solves: Without requiring the normalization constant, just being able to compute $\tilde\pi(x)$ (or its log), we can construct a stochastic process that “stays at $\pi$ in the long run” to draw samples.

Comparison with Other Approaches (Intuition):

- Variational Inference (VI): Fast, scalable, but approximates with a “tractable family”, introducing approximation bias;

- SMC/Particle Methods: Suitable for sequential problems, but design and resampling/annealing are complex;

- MCMC: Asymptotically Unbiased (can arbitrarily approximate $\pi$ if run long enough), but samples are correlated, computation can be expensive, and requires diagnostics/tuning.

Example

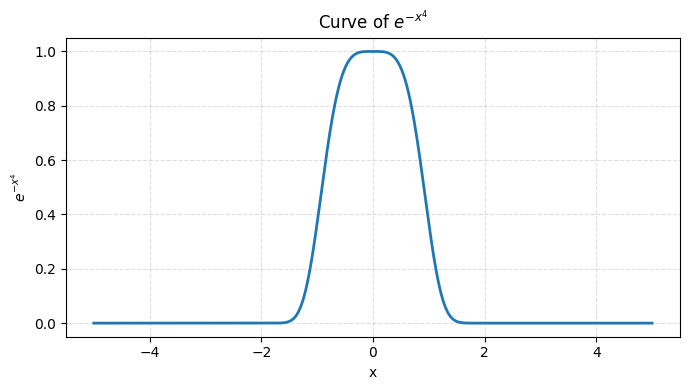

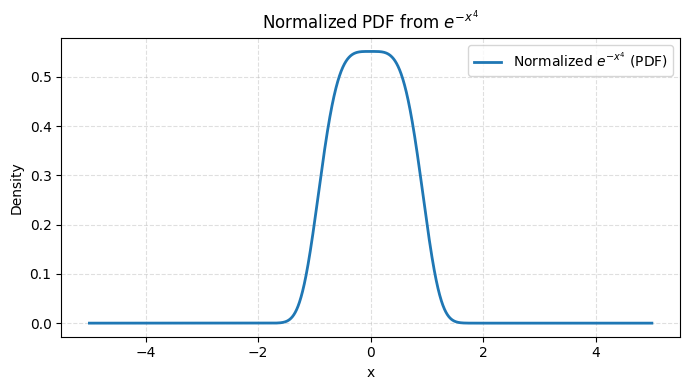

Suppose we want to sample from the following distribution:

$$ \pi(x) \propto e^{-x^4}, \quad x \in \mathbb{R}. $$- This is a “super sharp” unimodal distribution.

- Normalization constant $Z=\int e^{-x^4}\,dx$ is unknown (cannot be solved by hand).

- Want to compute expectation $\mathbb{E}[X^2]$.

👉 Problem:

- Direct integration is impossible (analytically intractable).

- Rejection Sampling needs a “suitable envelope function”, but the tail here is very heavy, hard to find.

👉 Intuitive Conclusion: This is where MCMC shines: As long as we can compute $\tilde\pi(x)=e^{-x^4}$, i.e., the unnormalized density, we can design a Markov chain to converge to it.

# Plot e^{-x^4}

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Domain range (-5 to 5 is enough to see main shape)

x = np.linspace(-5, 5, 4001)

y = np.exp(-x**4)

plt.figure(figsize=(7, 4))

plt.plot(x, y, lw=2)

plt.title(r"Curve of $e^{-x^4}$")

plt.xlabel("x")

plt.ylabel(r"$e^{-x^4}$")

plt.grid(True, ls="--", alpha=0.4)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Normalize e^{-x^4} to make it a Probability Density Function (PDF)

Z = np.trapezoid(y, x) # Numerical integration

pdf = y / Z

plt.figure(figsize=(7, 4))

plt.plot(x, pdf, lw=2, label="Normalized $e^{-x^4}$ (PDF)")

plt.title(r"Normalized PDF from $e^{-x^4}$")

plt.xlabel("x")

plt.ylabel("Density")

plt.grid(True, ls="--", alpha=0.4)

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

From Markov Chain to Sampling

In short, by constructing a “correct Markov chain”, its stationary distribution becomes the target distribution; trajectory’s long-term distribution ≈ target distribution.

Turning Sampling into “Building a Chain”

Let state space be $\mathsf{X}$, want samples from target distribution $\pi$. We don’t sample directly, but construct a transition kernel $P(x,A)=\Pr(X_{t+1}\in A\mid X_t=x)$, making $\pi$ its Stationary Distribution (invariant):

$$ \pi(A) \;=\; \int_{\mathsf{X}} \pi(dx)\,P(x,A),\quad \forall A. $$Intuition: If you randomly pick a start point under $\pi$, then take a step according to $P$, the distribution remains unchanged. Such a “distribution-invariant” random walk, keeps walking, keeps staying on $\pi$.

Ensuring “Reachable, Aperiodic, Forgetting Start”

“Stationary” alone is not enough; we also need the chain to converge to $\pi$. Common sufficient conditions:

- Irreducible: Can reach any “mass” region from anywhere with positive probability in finite steps;

- Aperiodic: Not stuck in fixed cycles;

- Reasonable “Recurrence” (Harris recurrence etc. technical conditions).

With these, classic results tell us: regardless of initial distribution, as time $t\to\infty$, distribution $P^t(x_0,\cdot)$ converges to $\pi$ in Total Variation distance:

$$ \big\|P^t(x_0,\cdot)-\pi\big\|_{\mathrm{TV}}\to 0. $$So, discard early samples (burn-in), subsequent trajectory is approximately from $\pi$.

Why “Unnormalized is Fine”

Many MCMC constructions only need the ratio $\tilde\pi(x)\propto \pi(x)$. The reason lies in Detailed Balance / Reversibility (see next section): using only the ratio $\tilde\pi(y)/\tilde\pi(x)$ ensures “symmetric flow”, thereby getting $\pi$ as stationary distribution. No need for $Z$ is the key advantage of MCMC.

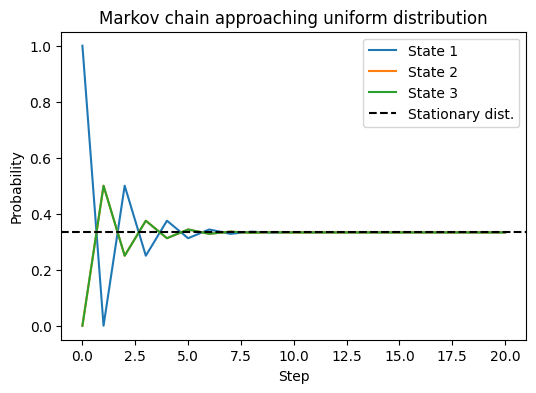

Example

To avoid introducing specific algorithms, determining let’s use the most familiar distribution: Uniform Distribution to illustrate.

Suppose target distribution is

$$ \pi(x) = \text{Uniform}\{1,2,3\}. $$We design a Markov chain:

- Walk among 3 states: 1, 2, 3;

- At each position, jump to another position with equal probability;

- E.g., at 1, jump to 2 with prob 0.5, to 3 with prob 0.5.

👉 The transition matrix P:

$$ P=\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0.5 & 0.5 \\ 0.5 & 0 & 0.5 \\ 0.5 & 0.5 & 0 \end{bmatrix}. $$Let’s run it and see how its distribution evolves.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Transition Matrix P

P = np.array([

[0.0, 0.5, 0.5],

[0.5, 0.0, 0.5],

[0.5, 0.5, 0.0]

])

# Initial distribution: All in state 1

dist = np.array([1.0, 0.0, 0.0])

history = [dist]

# Evolve 20 steps

for t in range(20):

dist = dist @ P

history.append(dist)

history = np.array(history)

# Theoretical stationary distribution (Uniform)

pi = np.array([1/3, 1/3, 1/3])

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(6,4))

for i in range(3):

plt.plot(history[:,i], label=f"State {i+1}")

plt.axhline(pi[0], color="k", linestyle="--", label="Stationary dist.")

plt.xlabel("Step")

plt.ylabel("Probability")

plt.title("Markov chain approaching uniform distribution")

plt.legend()

plt.show()

We can see:

- Initially distribution is all in state 1;

- As steps increase, three curves gradually approach $1/3$;

- Finally converges to stationary distribution (Uniform).

👉 Intuition: Markov chain’s “walking” allows us to sample from $\pi$ by relying on “long-term stay proportion” even if we don’t sample directly from $\pi$.

Theory and Intuition

Why it works, why it converges

In short,

- Stationary distribution exists, and satisfies detailed balance → Correctness.

- Convergence speed (Mixing time) affects sample quality.

- Smaller auto-correlation, larger ESS, “more efficient” chain.

Detailed Balance (Reversibility) and Stationarity

If there exists $\pi$ such that

$$ \pi(dx)\,P(x,dy) \;=\; \pi(dy)\,P(y,dx) \quad (\text{Symmetric Flow}) $$Then the chain is called reversible with respect to $\pi$, implying $\pi$ is a stationary distribution.

Intuition: Starting from $\pi$, the joint distribution of a forward step is same as a “backward step”, overall “no net flow”, so the steady state is “undisturbed”.

Many MCMC algorithms (MH, Gibbs, HMC, etc.) explicitly or implicitly construct this reversibility/invariance.

Convergence: Ergodic Theorem, LLN, CLT

When the chain is Ergodic (irreducible, aperiodic, and properly recurrent), we have:

Ergodic Theorem / Markov Chain Law of Large Numbers

$$ \frac{1}{T}\sum_{t=1}^T f(X_t) \;\xrightarrow{a.s.}\; \mathbb{E}_\pi[f(X)]. $$This guarantees using trajectory mean to estimate expectation is consistent.

Central Limit Theorem (CLT) (under geometric ergodicity etc. conditions)

$$ \sqrt{T}\Big(\bar f_T-\mathbb{E}_\pi[f]\Big)\ \Rightarrow\ \mathcal N\!\Big(0,\ \sigma_f^2\Big), $$Where

$$ \sigma_f^2 \;=\; \mathrm{Var}_\pi(f)\Big(1+2\sum_{k=1}^\infty \rho_k\Big), $$$\rho_k$ is the auto-correlation at lag $k$. Define Integrated Autocorrelation Time (IACT)

$$ \tau_{\text{int}} \;=\; 1+2\sum_{k\ge1}\rho_k, $$Then Effective Sample Size $\mathrm{ESS}\approx T/\tau_{\text{int}}$. Intuition: Stronger correlation (slow decay of $\rho_k$) means each sample has lower information, smaller ESS.

Mixing Time, Spectral Gap, and Geometric Convergence

Mixing Time characterizes approach speed of $P^t$ to $\pi$, commonly defined by TV distance:

$$ \tau(\varepsilon)\;=\;\min\{t:\ \sup_{x_0}\|P^t(x_0,\cdot)-\pi\|_{\mathrm{TV}}\le \varepsilon\}. $$For finite reversible chains, convergence speed is closely related to Spectral Gap $\gamma=1-\lambda_\star$ (second largest eigenvalue modulus $\lambda_\star$): $\tau(\varepsilon)$ typically scales as $\frac{1}{\gamma}\log(1/\varepsilon)$. Intuition: Large $\gamma$ ⇒ “Weak memory, fast forgetting”, faster mixing.

Conductance / Bottleneck characterizes “difficulty of crossing regions”, related to $\gamma$ via Cheeger inequality. Intuition: Multi-modal distribution, deep “valleys” between peaks ⇒ Small conductance ⇒ Slow mixing (easy to get “stuck in a mode”).

Burn-in, Thinning, Diagnostics (From Theory to Practice)

Burn-in: Early samples “not yet close to $\pi$” bias the estimate, discarding an initial segment is usually safer.

Thinning: “Subsampling” to save storage/reduce correlation, but from variance minimization perspective not strictly necessary; often better to keep all samples and use IACT/ESS for correct variance estimation.

Diagnostics (Intuition-driven):

- Trace: Wandering freely without obvious drift?

- ACF/ESS: Does correlation decay fast enough?

- Multi-chain R-hat: Do chains from multiple starting points mix together?

- Multi-modal: Any pattern of “stuck in mode” (long stay + sudden jump)?

Why MCMC can “Walk and Stay in High Density Areas”

View $\pi$ as Boltzmann distribution: $\pi(x)\propto e^{-U(x)}$, $U(x)=-\log \tilde\pi(x)$ looks like “energy landscape”. MCMC is like random thermal motion in the landscape:

- More willing to stay in Low Energy (High Density) regions;

- But through mechanisms like “perturbation/momentum/accept-reject”, still has chance to cross energy barriers to explore other regions;

- As long as mechanism guarantees invariant distribution is $\pi$ and chain is ergodic, long-term statistics will be correct.

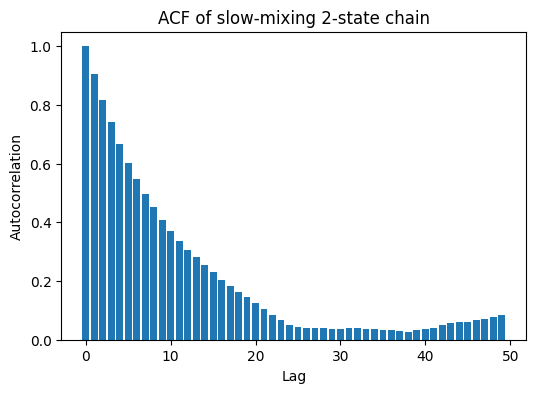

Example

Let’s build a “Slow Mixing” chain:

- States $\{0,1\}$,

- From 0, stay with prob 0.95, jump to 1 with prob 0.05;

- From 1, same logic.

👉 Although its stationary distribution is still uniform $[0.5,0.5]$, “correlation” is very strong.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Construct 2-state chain (Sticky)

P_slow = np.array([

[0.95, 0.05],

[0.05, 0.95]

])

# Simulate trajectory

T = 5000

x = np.zeros(T, dtype=int)

for t in range(1, T):

x[t] = np.random.choice([0,1], p=P_slow[x[t-1]])

# Compute Auto-Correlation Function (ACF)

def autocorr(x, lag):

n = len(x)

x_mean = np.mean(x)

num = np.sum((x[:n-lag]-x_mean)*(x[lag:]-x_mean)) # Auto-covariance

den = np.sum((x-x_mean)**2) # Variance

return num/den

lags = np.arange(50)

acfs = [autocorr(x, lag) for lag in lags]

# Plot

plt.figure(figsize=(6,4))

plt.bar(lags, acfs)

plt.xlabel("Lag")

plt.ylabel("Autocorrelation")

plt.title("ACF of slow-mixing 2-state chain")

plt.show()

Here you can see:

- Auto-Correlation Function (ACF) decays very slowly;

- Means adjacent samples are highly dependent, Effective Sample Size (ESS) is far less than total steps.

👉 Intuitive Summary:

- Markov chain will definitely converge to stationary distribution (if conditions met);

- But “Mixing Speed” varies: some equalize in few steps, some drag on;

- In MCMC, slow mixing chain has poor efficiency, resulting samples have “little information”.

Critical Indicators in Practice (No Algorithms Yet)

Only need $\tilde\pi(x)$: Can compute log-density up to constant, then MCMC is go.

Three things must be balanced:

- Invariance ($\pi$ is stationary) — if not invariant then long-term wrong;

- Reachable (Irreducible/Aperiodic) — if unreachable then pointless;

- Fast Mixing (Spectral gap/Conductance/Small IACT) — otherwise ESS too low, cost too high.

Error Assessment: Use IACT/ESS + Markov Chain CLT for MC variance and confidence intervals.

Multi-modal Warning: Multi-modal + high-dim correlation often leads to Metastability, need algorithms or strategies better at “climbing hills crossing valleys” (Tempering, Gradient methods, etc.) to improve conductance.

Summary

Purpose: Estimate expectation/sample from complex $\pi$; No normalization constant needed.

Method: Build a chain $P$ such that $\pi$ is invariant (often using Detailed Balance).

Condition: Irreducible + Aperiodic + Proper Recurrence ⇒ $P^t\to\pi$.

Assessment:

- Convergence (after burn-in) + Mixing (IACT/ESS, Spectral gap, Conductance)

- Diagnostics: Trace, ACF, R-hat, Multi-chain consistency

Error: $\mathrm{ESS}\approx T/\tau_{\text{int}}$, CLT gives confidence intervals.

Difficulty: Multi-modal/High-dim correlation ⇒ Slow mixing; Need better “moving strategies”.

Scan to Share

微信扫一扫分享