Gibbs Sampler is an algorithm to build a Markov Chain having a given N-dimension limit distribution, exploring its conditional distribution.

The “Divide and Conquer” Intuition

Recap of Pain: In high-dimensional space (e.g., 100D), making a single acceptable proposal ($x_{new}$) with MH sampling is incredibly hard. It’s like trying to guess 100 coin flips correctly at once.

- While we can reduce multi-dimensional problems to one dimension via combination, when dimensions and state spaces are large, the resulting 1D state space becomes unmanageably huge.

Gibbs Strategy: Dimensionality Reduction (Divide and Conquer).

- We don’t change all dimensions at once.

- We update only one dimension at a time, treating the other 99 as constants (fixed).

Intuitive Analogy:

- MH Algorithm: Jumping randomly on a map like a helicopter.

- Gibbs Sampling: Walking on the streets of Manhattan, only moving East-West or North-South (Axis-aligned moves).

The MH Dilemma: High-Dimensional “Lottery”

Imagine you are doing a 100-dimensional sampling task (like generating a 10x10 pixel image, where each pixel is a dimension).

In Metropolis-Hastings (MH), you need a proposal distribution $Q$. If you try to update all 100 pixels at once:

- You are asking: “Hey, does this new combination of 100 numbers look like a reasonable image?”

- The probability of randomly guessing a “good point” in 100D space is as low as winning the lottery!

- Result: Your proposals are almost always rejected. Acceptance rate near 0, computer runs for days with no movement.

Gibbs Strategy: One Thing at a Time

Gibbs Sampling says: “Don’t be greedy. Since guessing 100 numbers is too hard, how about guessing just 1?”

Its logic:

- Lock dimensions 2 to 100 (pretend they are constants).

- Now, the question becomes: “Given everyone else is fixed, what is the best value for dimension 1?”

- This is a 1-dimensional problem! Too easy. We draw a number directly from this Conditional Distribution.

- Update dimension 1. Next, lock 1, 3…100, update dimension 2…

Core Philosophy: Break a complex $N$-dimensional problem into $N$ simple $1$-dimensional problems.

Math perspective: Convert Joint Distribution to Conditional Distributions.

Visual Intuition: Manhattan Walk

To visualize the trajectory, let’s compare MH and Gibbs on a 2D map. Assume we are climbing a mountain (Target $\pi$), peak is at top-right.

🚁 MH Algorithm: Helicopter Jump

- Action: Disregards terrain, throws a probe in a random direction (diagonal, far).

- Trajectory: Can move at any angle.

- Cost: If it lands on a cliff (low prob), it bounces back (Rejected).

🚶 Gibbs Sampling: Manhattan Walk

- Action: Imagine walking in Manhattan’s grid city. You can’t walk through walls or diagonally. You follow streets (axes).

- Trajectory:

- Move along X-axis (Update $x$, fixed $y$).

- Move along Y-axis (Update $y$, fixed $x$).

- Repeat.

- Feature: Trajectory is always orthogonal zig-zag, like climbing stairs.

Why is it Easy? (Slicing Thought)

You might ask: “Just changing direction, why no rejection needed?”

Imagine a 2D Normal distribution (like a hill). Each step of Gibbs is actually “Slicing” the hill.

- When you fix $y=5$, you slice the hill horizontally at $y=5$.

- The cross-section is a 1D curve.

- Gibbs says: “Please sample directly from this 1D curve.”

- Since you sample directly from the valid slice, the result is always valid. Acceptance Rate = 100%!

Mathematical Principles

Joint Distribution Equivalent to All “Full Conditionals”

Usually we think: Joint Distribution $P(x_1, \dots, x_n)$ holds all info. From it, deriving marginals or conditionals is easy. But the reverse isn’t intuitive: If I give you all “Full Conditionals” $P(x_i | x_{-i})$, can you uniquely reconstruct the original Joint Distribution?

Answer: Yes, under a condition (Positivity Assumption). This is Brook’s Lemma.

Proof

Step 1: Joint $\Rightarrow$ Conditionals (Easy)

This is just definition.

$$ P(x_i | x_{-i}) = \frac{P(x_1, \dots, x_n)}{P(x_{-i})} = \frac{P(x_1, \dots, x_n)}{\int P(x_1, \dots, x_n) dx_i} $$Obviously, given Joint, Conditionals are determined.

Step 2: Conditionals $\Rightarrow$ Joint (Hard: Brook’s Lemma)

This is the core of Gibbs. Without this, we wouldn’t know if sampling conditionals converges to the correct joint.

We need to prove: Full Conditionals uniquely determine Joint Distribution (up to a constant).

Let’s use Bivariate (2D) case ($x, y$).

- Goal: Find expression for $\frac{P(x, y)}{P(x_0, y_0)}$, where $(x_0, y_0)$ is an arbitrary reference point.

- Identity: Break ratio into two steps (via $(x_0, y)$): $$\frac{P(x, y)}{P(x_0, y_0)} = \frac{P(x, y)}{P(x_0, y)} \cdot \frac{P(x_0, y)}{P(x_0, y_0)}$$

- Expand Term 1 (Bayes): $P(x, y) = P(x | y) P(y)$. $$\frac{P(x, y)}{P(x_0, y)} = \frac{P(x | y) \cancel{P(y)}}{P(x_0 | y) \cancel{P(y)}} = \frac{P(x | y)}{P(x_0 | y)}$$ See! Marginal $P(y)$ cancels! Only conditionals remain.

- Expand Term 2: $P(x_0, y) = P(y | x_0) P(x_0)$. $$\frac{P(x_0, y)}{P(x_0, y_0)} = \frac{P(y | x_0) \cancel{P(x_0)}}{P(y_0 | x_0) \cancel{P(x_0)}} = \frac{P(y | x_0)}{P(y_0 | x_0)}$$ Marginal $P(x_0)$ cancels too!

- Combine (Brook’s Lemma for 2D): $$P(x, y) \propto \frac{P(x | y)}{P(x_0 | y)} \cdot \frac{P(y | x_0)}{P(y_0 | x_0)}$$

Conclusion: The RHS contains only conditional distributions. Thus, knowing $P(x|y)$ and $P(y|x)$ uniquely determines the shape of $P(x,y)$.

General N-Dim (Brook’s Lemma)

Ideally walking steps from $\mathbf{x}^0$ to $\mathbf{x}$: $(0,0,0) \to (x_1, 0, 0) \to (x_1, x_2, 0) \to (x_1, x_2, x_3)$.

Formula:

$$P(\mathbf{x}) \propto \prod_{i=1}^n \frac{P(x_i | x_1, \dots, x_{i-1}, x_{i+1}^0, \dots, x_n^0)}{P(x_i^0 | x_1, \dots, x_{i-1}, x_{i+1}^0, \dots, x_n^0)}$$Crucial Prerequisite: Positivity Condition

Did you spot a bug? We are dividing! Denominators like $P(x_0 | y)$ appear. If probability is 0 somewhere, dividing by 0 is illegal.

This is the Hammersley-Clifford Theorem requirement: Joint distribution must satisfy Positivity Assumption. i.e., For any $x_i$, if meaningful marginally, their combination $(x_1, \dots, x_n)$ must have prob > 0.

Counter-example: Chessboard where only white squares have prob=1, black=0.

- $P(x|y)$ tells you where white squares are in a row.

- But you can’t compare probability of white squares in different rows because “paths” are blocked by black squares (prob 0 abyss).

Why No Rejection? (Why Acceptance is 100%?)

Gibbs Sampling is essentially Metropolis-Hastings with acceptance rate $\alpha=1$.

Intuitive: Why no “Audit”?

- Metropolis (Blind Guess): You grab a shirt with eyes closed (Proposal $Q$). Open eyes, check fit ($\pi$). If bad, throw back (Reject). Blindness requires audit.

- Gibbs (Tailor-made): You go to a tailor. Tailor measures you (Fixed $x_{-i}$), makes shirt exactly to size (Sample from $P(x_i | x_{-i})$). Does this custom shirt need “audit”? No. It’s born valid.

Math Proof: MH Formula Cancellation

Assume variables $x, y$. Current: $(x, y)$

- Action: Update $x$, fix $y$.

- Gibbs Proposal: Sample new $x^*$ from full conditional. $$Q(\text{new} | \text{old}) = Q(x^*, y | x, y) = P(x^* | y)$$

Note: Depends only on $y$, not old $x$.

Reverse proposal:

$$Q(\text{old} | \text{new}) = Q(x, y | x^*, y) = P(x | y)$$Substitute into MH Acceptance:

$$\alpha = \frac{\pi(\text{new})}{\pi(\text{old})} \times \frac{Q(\text{old} | \text{new})}{Q(\text{new} | \text{old})}$$- Target $\pi$ is Joint $P(x, y)$. $$\text{Target Ratio} = \frac{P(x^*, y)}{P(x, y)}$$

- Proposal $Q$. $$\text{Proposal Ratio} = \frac{P(x | y)}{P(x^* | y)}$$

- Combine ($P(a,b) = P(a|b)P(b)$): $$A = \frac{P(x^*, y)}{P(x, y)} \times \frac{P(x | y)}{P(x^* | y)} = \frac{\mathbf{P(x^* | y)} \cdot \mathbf{P(y)}}{\mathbf{P(x | y)} \cdot \mathbf{P(y)}} \times \frac{\mathbf{P(x | y)}}{\mathbf{P(x^* | y)}}$$

- The Cancellation:

- $P(y)$: Cancels.

- $P(x^* | y)$ and $P(x | y)$: Cancel cross-wise.

- Result: $$A = 1$$

So $\alpha = 1$.

Algorithm Flow

To sample from $n$-dim joint $P(x_1, \dots, x_n)$.

- Initialization: Pick start $\mathbf{x}^{(0)}$.

- Iteration Loop ($t=1 \dots T$): Update each component sequentially. Updated values used immediately.

- Update Dim 1: Sample $x_1^{(t)} \sim P(x_1 \mid x_2^{(t-1)}, \dots, x_n^{(t-1)})$

- Update Dim 2: Sample $x_2^{(t)} \sim P(x_2 \mid x_1^{(t)}, x_3^{(t-1)}, \dots)$ …

- Update Dim $n$: Sample $x_n^{(t)} \sim P(x_n \mid x_1^{(t)}, \dots, x_{n-1}^{(t)})$

- Collect: $\mathbf{x}^{(t)}$ is a sample.

Update Strategies

- Systematic Scan: Order $1 \to 2 \to \dots \to n$. Most common.

- Random Scan: Randomly pick dimension $i$ to update. Easier for some proofs.

- Blocked Gibbs: Group correlated variables (e.g., $x_1, x_2$) and sample joint $P(x_1, x_2 | \dots)$. Solves slow mixing in correlated features.

Code Practice

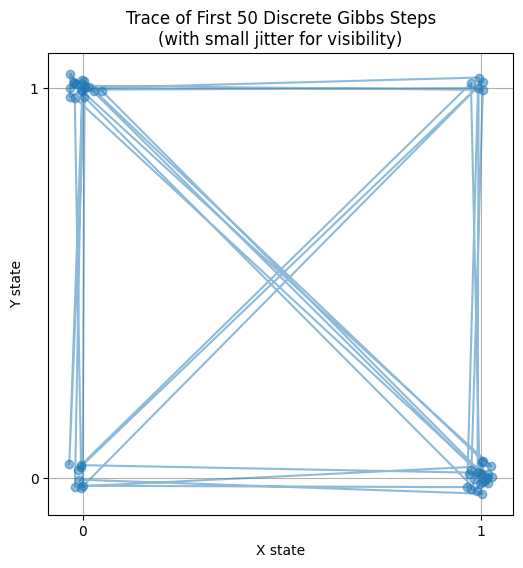

Discrete: Bivariate System

Two variables $x, y \in \{0, 1\}$. Known joint probability table:

| x | y | P(x,y) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0.1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0.4 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.3 |

| 1 | 1 | 0.2 |

Goal: Sample to match these frequencies using only local conditional rules.

Conditionals:

- Given $y$, $P(x|y)$:

- $y=0$: $P(x=0|0) = 0.1/(0.1+0.3) = 0.25$, $P(x=1|0)=0.75$

- $y=1$: $P(x=0|1) = 0.4/(0.4+0.2) \approx 0.67$, $P(x=1|1)=0.33$

- Given $x$, $P(y|x)$:

- $x=0$: $P(y=0|0) = 0.2$, $P(y=1|0)=0.8$

- $x=1$: $P(y=0|1) = 0.6$, $P(y=1|1)=0.4$

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# 1. Conditionals

def sample_x_given_y(y):

if y == 0:

return np.random.choice([0, 1], p=[0.25, 0.75])

else:

return np.random.choice([0, 1], p=[0.67, 0.33])

def sample_y_given_x(x):

if x == 0:

return np.random.choice([0, 1], p=[0.2, 0.8])

else:

return np.random.choice([0, 1], p=[0.6, 0.4])

# 2. Gibbs Loop

def discrete_gibbs(n_iter):

samples = []

x, y = 0, 0 # Init

for _ in range(n_iter):

x = sample_x_given_y(y) # Update x

y = sample_y_given_x(x) # Update y

samples.append((x, y))

return np.array(samples)

# 3. Run

n_iter = 10000

results = discrete_gibbs(n_iter)

# Frequency Analysis

unique, counts = np.unique(results, axis=0, return_counts=True)

frequencies = counts / n_iter

print("--- Discrete Gibbs Results ---")

for state, freq in zip(unique, frequencies):

print(f"State {state}: Freq {freq:.4f}")

# Visualize first 50 steps

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

plt.plot(results[:50, 0] + np.random.normal(0, 0.02, 50),

results[:50, 1] + np.random.normal(0, 0.02, 50),

'o-', alpha=0.5)

plt.xticks([0, 1])

plt.yticks([0, 1])

plt.title("Trace of First 50 Discrete Gibbs Steps\n(with small jitter for visibility)")

plt.xlabel("X state")

plt.ylabel("Y state")

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

--- Discrete Gibbs Results ---

State [0 0]: Freq 0.1017

State [0 1]: Freq 0.4054

State [1 0]: Freq 0.2928

State [1 1]: Freq 0.2001

- Fast Convergence: Instantly locks to target propertions.

- Trajectory: Jumps between (0,0), (0,1), (1,0), (1,1) strictly along axes.

- Application: Core of Image Denoising (Ising) and NLP (LDA).

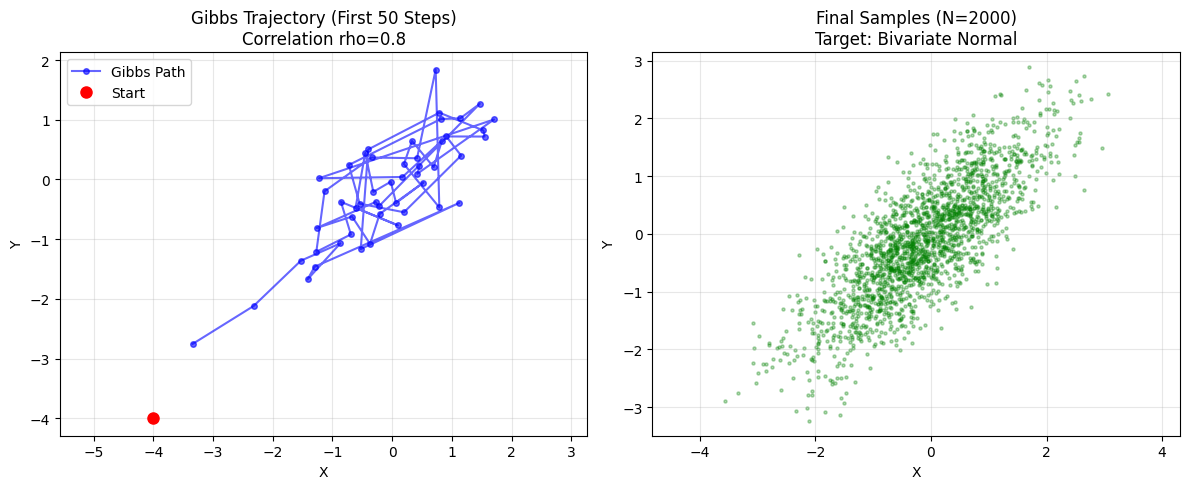

Continuous: Bivariate Normal

Target $(x, y)$: Standard Bivariate Normal.

- $\mu_x = 0, \mu_y = 0, \sigma_x = 1, \sigma_y = 1$

- Correlation $\rho$.

Direct formula is messy. Gibbs is easy. Conditionals:

$$P(x | y) = \mathcal{N}(\text{mean}=\rho y, \text{var}=1-\rho^2)$$$$P(y | x) = \mathcal{N}(\text{mean}=\rho x, \text{var}=1-\rho^2)$$Intuition:

- Mean $\rho y$: If $y$ is positive and $\rho>0$, $x$ is likely positive. Center shifts.

- Var $1-\rho^2$: If correlated ($\rho \to 1$), variance $\to 0$. $x$ is locked by $y$.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# --- 1. Params ---

rho = 0.8 # Correlation

n_samples = 2000

start_x, start_y = -4.0, -4.0 # Far corner start

# --- 2. Gibbs Sampler ---

def run_gibbs_sampler(n, rho, start_x, start_y):

samples = np.zeros((n, 2))

x, y = start_x, start_y

cond_std = np.sqrt(1 - rho**2)

for i in range(n):

# A. Fix y, sample x

x = np.random.normal(loc=rho * y, scale=cond_std)

# B. Fix x, sample y (use new x)

y = np.random.normal(loc=rho * x, scale=cond_std)

samples[i] = [x, y]

return samples

# Run

chain = run_gibbs_sampler(n_samples, rho, start_x, start_y)

# --- 3. Viz ---

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 5))

# Plot 1: Trace (First 50)

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

plt.plot(chain[:50, 0], chain[:50, 1], 'o-', alpha=0.6, color='blue', markersize=4, label='Gibbs Path')

plt.plot(start_x, start_y, 'ro', label='Start', markersize=8)

plt.title(f"Gibbs Trajectory (First 50 Steps)\nCorrelation rho={rho}")

plt.xlabel("X")

plt.ylabel("Y")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.axis('equal')

# Plot 2: Final Scatter

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

plt.scatter(chain[:, 0], chain[:, 1], s=5, alpha=0.3, color='green')

plt.title(f"Final Samples (N={n_samples})\nTarget: Bivariate Normal")

plt.xlabel("X")

plt.ylabel("Y")

plt.axis('equal')

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Trajectory (Left Plot):

- Orthogonal Moves: Steps are purely horizontal or vertical. Zig-zag.

- Burn-in: Starts at $(-4, -4)$ and quickly (5-10 steps) climbs to the center $(0,0)$.

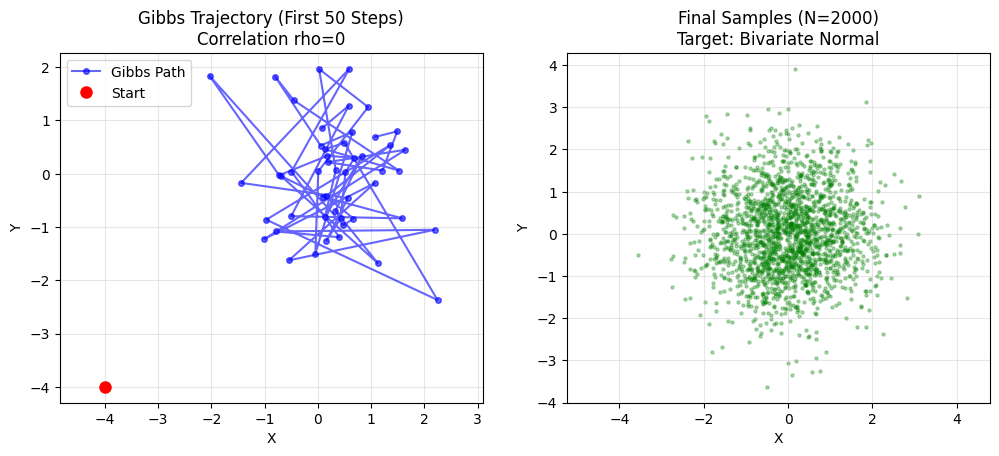

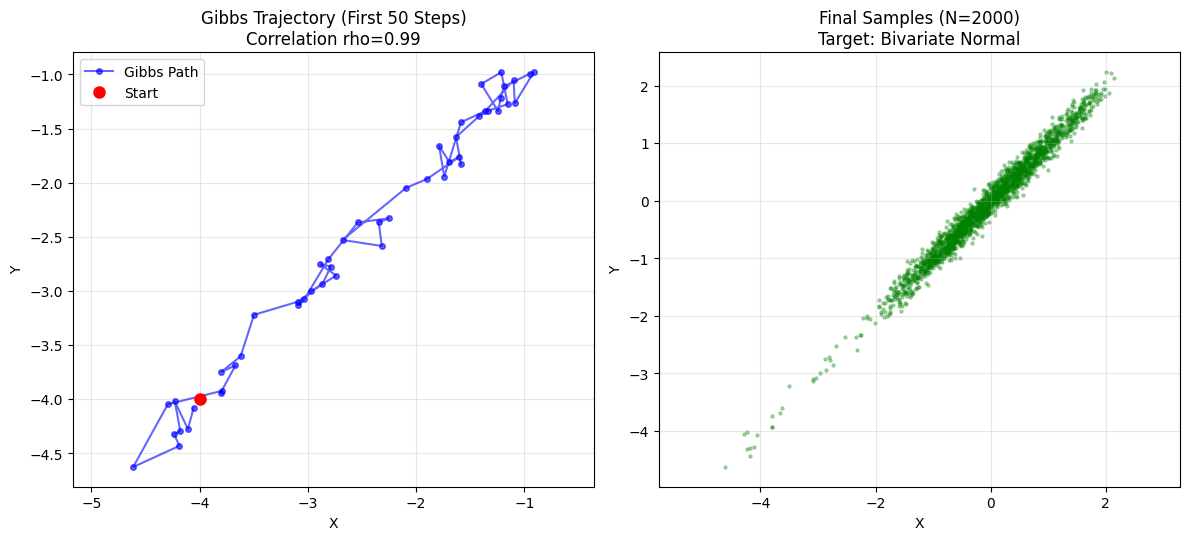

The Kryptonite: High Correlation

- Defect: 100% acceptance $\neq$ Efficiency.

- Scenario: High correlation ($\rho = 0.99$). Distribution is a thin canyon.

- Dilemma: Gibbs moves orthogonally. In a diagonal canyon, it must take tiny baby steps (staircase). Slow Mixing.

- Solution: Blocked Gibbs / Reparameterization.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# --- 1. Params ---

rhos = {0: 'No Corr', 0.99: 'High Corr'}

n_samples = 2000

start_x, start_y = -4.0, -4.0

# --- 2. Gibbs Sampler (Reusable) ---

# ... (same function)

# Run

index = 1

for rho, rho_label in rhos.items():

chain = run_gibbs_sampler(n_samples, rho, start_x, start_y)

# --- 3. Viz ---

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 10))

# Trace

plt.subplot(2, 2, index)

plt.plot(chain[:50, 0], chain[:50, 1], 'o-', alpha=0.6, color='blue', markersize=4, label='Gibbs Path')

plt.plot(start_x, start_y, 'ro', label='Start', markersize=8)

plt.title(f"Gibbs Trajectory (First 50 Steps)\nCorrelation rho={rho}")

plt.xlabel("X")

plt.ylabel("Y")

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.axis('equal')

index += 1

# Scatter

plt.subplot(2, 2, index)

plt.scatter(chain[:, 0], chain[:, 1], s=5, alpha=0.3, color='green')

plt.title(f"Final Samples (N={n_samples})\nTarget: Bivariate Normal")

plt.xlabel("X")

plt.ylabel("Y")

plt.axis('equal')

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

index += 1

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

- rho = 0: Circle. Gibbs jumps freely. Fast mixing.

- rho = 0.99: Thin line. Gibbs takes tiny steps along diagonal. Slow convergence.

Scan to Share

微信扫一扫分享